For many King Air pilots, most of our flying utilizes the Global Positioning System. What would happen if the entire National Airspace System (NAS) relied solely on GPS and the system broke down due to technical issues or nefarious intent?

GPS is susceptible to interference, jamming, spoofing or solar events, any of which can disrupt aircraft navigation. Despite these vulnerabilities, we have been hearing for years that the Federal Aviation Administration is removing ground-based navigation equipment relying on GPS for the NAS.

In 2006, the FAA started the transition to performance-based navigation (PBN) primarily using GPS and area navigation, or RNAV. The FAA has been removing selected VORs – stations emitting very high frequency omni-directional range signals – from service and replacing them with flight procedures and route structure based on PBN.

The FAA realized that a VOR minimum operational network (MON) would need to be retained to provide a backup during GPS interference. With the MON as a backup, basic conventional navigation would be possible if GPS failed.

Navigation using the MON will not be as efficient as the new PBN route structure, but use of the MON will provide nearly continuous VOR signal across the NAS.

To repurpose the contiguous United States VOR network from the primary means of navigation to a backup, the VOR signal must be available starting at 5,000 feet above ground level. Coverage will exist below 5,000 feet but may not be continuous. To provide the required coverage, new VOR standard service volumes were established.

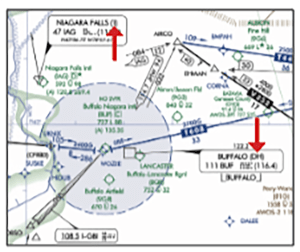

See Figure 1 for the previous standard service volumes and Figure 2 for the current list of SSV classifications. NAVAIDs with a single component SSV (VOR, DME, TACAN, NDB, NDB/DME) classification depict the name of the NAVAID first then the classification of the SSV in parentheses next on the IFR low-altitude en route charts, as shown in Figure 3. NAVAIDs with two component SSV (VOR/DME, VORTAC) classifications depict the name of the NAVAID first then the classification of the two SSVs in parentheses for each component on the IFR low chart. Figure 4 shows the VOR SSV in the first set of parentheses followed by the DME or TACAN SSV in the second set of parentheses.

Progress on new VOR standard service volumes

MON VORs will be flight inspected (see Figure 5) and their class codes changed to the new SSVs. To date, the majority of the 499 new VOR SSVs have been published.

VORs that do not meet the VOR MON criteria are targeted for discontinuance. By the end of 2024, 194 VORs of 303 targeted VORs were scheduled to be discontinued. By 2030, the FAA plans to reduce the total number of VOR stations in the contiguous United States to 580.

During a GPS disruption in the contiguous U.S., the MON will enable aircraft to navigate through the affected area or to a safe landing at a MON airport without reliance on GPS. Pilots can tune and identify a VOR at or above 5,000 feet AGL and navigate VOR-to-VOR or along airways through the interference or navigate to an airport within 100 nautical miles to fly an ILS, LOC or VOR approach.

What are MON airports?

The FAA has designated certain airports as MON airports as part of its plan to modernize the NAS and ensure the safety and efficiency of air travel. MON airports are strategically selected airports that maintain specific navigation and approach capabilities to support aircraft operations during GPS disruptions. The FAA considers several factors when designating MON airports, including:

Location: Airports are strategically located throughout the country to provide adequate coverage and accessibility.

Airport infrastructure: The airport must have the necessary infrastructure to support instrument approaches, such as runway lighting and communication systems.

Air traffic density: Airports with higher air traffic volumes are more likely to be designated as MON airports.

These airports have instrument approach procedures that are not reliant on GPS technology, such as ILS, LOC and VOR approaches. Users can navigate through an interference event or land at a MON airport without GPS, DME, ADF or surveillance. By providing a reliable backup navigation system, MON airports help mitigate the risks associated with GPS disruptions and maintain the continuity of air traffic operations. Users not equipped with GPS can still operate in the NAS, but likely with reduced efficiency. There are no changes to current equipment or flight plan filing requirements.

The FAA publishes a list of MON airports in the chart supplement (formerly known as the airport/facility directory). This publication is available in both printed and digital formats. You can also find information on MON airports through various online resources, such as FAA websites and aviation publications.

See Figure 6 for how the IFR Low Chart depicts MON airports with green “MON” text. Pilots are responsible for familiarizing themselves with these airports and their approach procedures. The FAA encourages pilots to use all available navigation resources, including GPS and ground-based systems, to maintain situational awareness and ensure safe flight operations.

Keep conventional navigation top of mind

The King Air is a very capable aircraft. It allows us to fly during the day, night, VFR, IFR and in icing conditions. Use of GPS is commonplace when flying in the King Air. It is a great, reliable tool. Loading an IFR flight plan into the GPS navigation unit is secondhand to us. Often “Cleared direct to …” after takeoff is heard from the controller. It seems like flying “direct to” is the only way we fly now. This can lead to dependency on GPS and complacency of conventional navigation. What happens when the GPS suddenly gives you a message “LOI” (Loss of Integrity) or “DR” (Dead Reckoning)? Now what?

Knowing that the FAA has a backup to GPS in the form of the VOR MON, how do we stay proficient with conventional navigation, using VOR, ILS and LOC in case we lose GPS?

One way to keep conventional navigation in the front of mind is to periodically file an IFR flight plan using Victor airways. In the note section of the flight plan state that you would like to remain on the filed route, no shortcuts. After loading the flight plan into the GPS navigation unit, review it and take note of any VORs on your route. Set up your NAV radios with the pertinent ground-based NAVAIDs for that flight. Try to keep up with the NAV frequency changes enroute. If you can display a bearing pointer, use that to verify the VOR course. It is interesting to see the difference between GPS and VOR course. When the controller gives you a clearance “direct to …” you can reply that you would like to stay on the filed route. If you don’t have a bearing pointer, try navigating using VORs only. Obviously, this would be a flight in which you were not in a hurry to get to your destination.

I have experienced the dreaded LOI and DR messages. There was panic at first but then the relief of knowing I was already set up with the VORs in the background. I continued using the VORs almost seamlessly. I didn’t have to scramble to find the proper VORs, frequencies or courses. Since I had been keeping up with the flight, situational awareness was already in place. I was lucky the outage happened while I was on a Victor airway.

As VORs are being decommissioned, more and more Victor airways are disappearing. They are being replaced with GPS-based RNAV routes called “T” routes (low-altitude RNAV routes). Jet routes are being replaced with “Q” routes (high-altitude RNAV routes). Remember, the MON system will retain enough conventional routes to cover GPS outages.

If my outage happened during a flight when I was off airway, I would have had to ask for a vector, possibly to the closest VOR. Maybe surveillance was out; I would now have to fly directly to a VOR and navigate using a Victor airway from then on. I may have had to shoot a VOR approach because the closest MON airport with an ILS was too far away.

When was the last time you intercepted and tracked a VOR radial, entered a holding pattern without the GPS or shot a VOR approach not using GPS? Asking your training provider to cover some of these topics in your next recurrent visit is another good way to stay proficient with conventional navigation.

The FAA’s plan to reduce ground-based navigation equipment is happening now. The MON system and our training to be proficient in conventional navigation gives us the knowledge, confidence and reassurance that we will need to be able to navigate our King Air in the event of a GPS disruption.

Pete Marx has more than 30 years of experience in the aviation industry, from flying as a captain and first officer on Beech 1900s, Jetstream 42s and Dash 8s for commuter airlines to flying cargo as a flight engineer and check airman in the Airbus 300 and DC-8 for DHL. He has been instructing in King Airs for the past 13 years and is currently an instructor at King Air Academy in Phoenix, Arizona.